How To Draw A Comet For Kids

Comets: Facts about the 'dirty snowballs' of space

Comets are icy bodies of frozen gases, rocks and dust left over from the formation of the solar system about 4.6 billion years ago. They orbit the sun in highly elliptical orbits that can take hundreds of thousands of years to complete.

As a comet approaches the sun, it heats up very quickly causing solid ice to turn directly into gas via a process called sublimation, according to the Lunar and Planetary Institute. The gas contains water vapor, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and other trace substances, and is eventually swept into the distinctive comet tail.

Scientists sometimes call comets dirty snowballs or snowy dirtballs, depending on whether they contain more ice material or rocky debris according to NASA.

Related: Amazing photos of Comet NEOWISE from Earth and space

According to NASA, as of September 2021, the current number of known comets is 3,743. Though billions more are thought to be orbiting the sun beyond Neptune in the Kuiper Belt and the distant Oort cloud far beyond Pluto.

Occasionally, a comet streaks through the inner solar system; some do so regularly, some only once every few centuries. Many people have never seen a comet, but those who have won't easily forget the celestial show.

What is a comet made of?

A comet primarily consists of a nucleus, coma, hydrogen envelope, dust and plasma tails. Scientists analyze these components to learn about the size and location of these icy bodies, according to ESA.

Nucleus

The nucleus is the solid core of a comet consisting of frozen molecules including water, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, methane and ammonia as well as other inorganic and organic molecules — dust. According to ESA the nucleus of a comet is usually around 10 kilometers across or less.

Coma

As a comet gets closer to the sun, the ice on the surface of the nucleus begins turning into gas, forming a cloud around the comet known as the coma. According to science website howstuffworks.com the coma is often 1,000 times larger than the nucleus.

Hydrogen envelope

Surrounding the coma is a hydrogen envelope that can be up to 6.2 million miles (10 million kilometers) long and is made from hydrogen atoms according to ESA. As the comet gets closer to the sun, the hydrogen envelope gets bigger.

Tails

There are two main types of comet tails, dust and gas. Comet tails are shaped by sunlight and the solar wind and always point away from the sun according to Swinburne University of Technology.

According to NASA, comet tails get longer as a comet approaches the sun and can end up millions of miles long. The dust tail is formed when solar wind pushes small particles in the coma into an elongated curved path. Whereas the ion tail is formed from electrically charged molecules of gas.

Comet tails may spray planets, as was the case in 2013 with Comet Siding Spring's close encounter with Mars.

We can see a number of comets with the naked eye when they pass close to the sun because their comas and tails reflect sunlight or even glow because of energy they absorb from the sun. However, most comets are too small or too faint to be seen without a telescope.

Comets leave a trail of debris behind them that can lead to meteor showers on Earth. For instance, the Perseid meteor shower occurs every year between August 9 and 13 when Earth passes through the orbit of Comet Swift-Tuttle.

Comet orbits

Astronomers classify comets based on the durations of their orbits around the sun. Short-period comets need roughly 200 years or less to complete one orbit, long-period comets take more than 200 years, and single-apparition comets are not bound to the sun, on orbits that take them out of the solar system, according to NASA. Recently, scientists have also discovered comets in the main asteroid belt — these main-belt comets might be a key source of water for the inner terrestrial planets.

Scientists think short-period comets, also known as periodic comets, originate from a disk-shaped band of icy objects known as the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune's orbit, with gravitational interactions with the outer planets dragging these bodies inward, where they become active comets. Long-period comets are thought to come from the nearly spherical Oort Cloud even further out, which get slung inward by the gravitational pull of passing stars. In 2017, scientists found there may be seven times more big long-period comets than previously thought.

Some comets, called sun-grazers, smash right into the sun or get so close that they break up and evaporate. Some researchers are also concerned that comets may pose a threat to Earth as well.

Naming a comet

Comets are generally named after their discoverer. For example, comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 got its name because it was the ninth short-periodic comet discovered by Eugene and Carolyn Shoemaker and David Levy. Spacecraft have proven very effective at spotting comets as well, so the names of many comets incorporate the names of missions such as SOHO or WISE.

Comets through history

In antiquity, comets inspired both awe and alarm, "hairy stars" resembling fiery swords that appeared unpredictably in the sky. Often, comets seemed to be omens of doom — the most ancient known mythology, the Babylonian "Epic of Gilgamesh," described fire, brimstone, and flood with the arrival of a comet, and the Roman emperor Nero saved himself from the "curse of the comet" by having all possible successors to his throne executed. This fear was not just limited to the distant past — in 1910, people in Chicago sealed their windows to protect themselves from what they thought was the comet's poisonous tail.

For centuries, scientists thought comets traveled in the Earth's atmosphere, but in 1577, observations made by Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe revealed they actually traveled far beyond the moon. Isaac Newton later discovered that comets move in elliptical, oval-shaped orbits around the sun, and correctly predicted that they could return again and again.

Chinese astronomers kept extensive records on comets for centuries, including observations of Halley's Comet going back to at least 240 B.C., historic annals that have proven valuable resources for later astronomers.

Comet missions

A number of missions have ventured to comets.

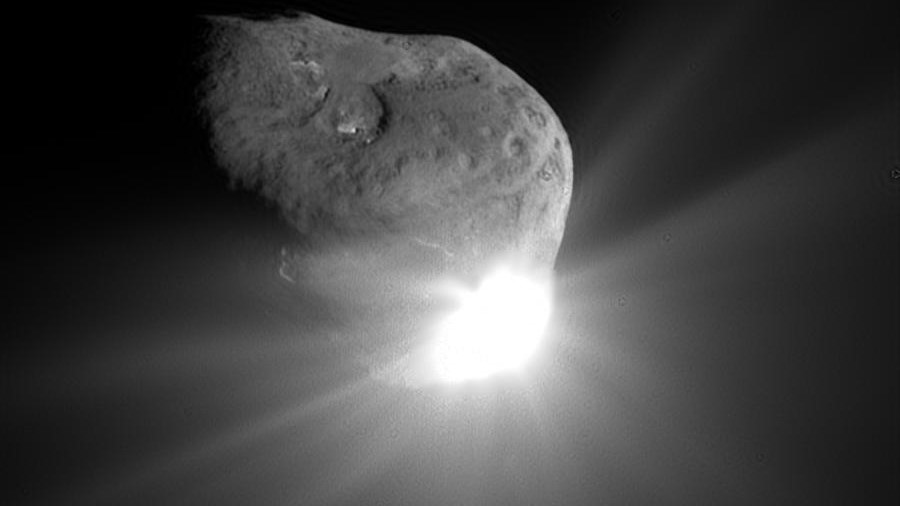

NASA's Deep Impact collided an impactor into Comet Tempel 1 in 2005 and recorded the dramatic explosion that revealed the interior composition and structure of the nucleus. The mission also included a flyby of Comet Hartley 2 and the remote sensing of Comet Garradd during an extended mission.

In 2009, NASA announced that samples returned from Comet Wild 2 during the Stardust mission revealed a building block of life — glycine. According to NASA, it was the first time an amino acid was found in a comet.

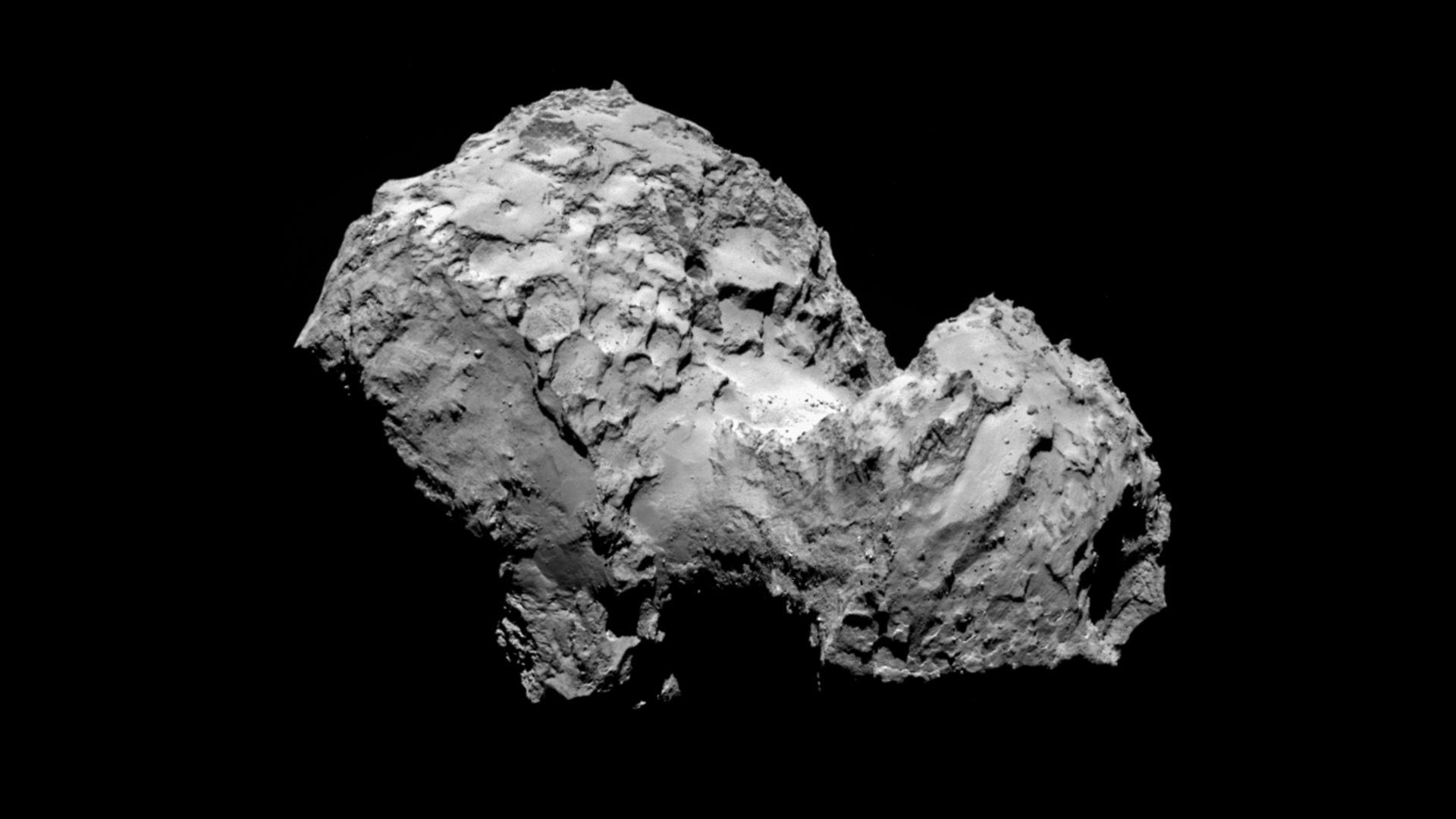

In 2014, the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft entered orbit around Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The Philae lander touched down on Nov 12, 2014. Among the Rosetta mission's many discoveries was the first detection of organic molecules on the surface of a comet; a strange song from Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko; the possibilities that the comet's odd shape may be due to it spinning apart, or resulting from two comets fusing together; and the fact that comets may possess hard, crispy outsides and cold but soft insides, just like fried ice cream. On Sept. 30, 2016, Rosetta intentionally crash-landed on the comet, ending its mission.

June 19, 2019, ESA selected the Comet Interceptor mission as the last "fast" or F-class mission. The new mission will intercept an as-yet-undiscovered comet as it enters the inner solar system. The mission consists of three spacecraft that will capture snapshots of the comet from different angles, creating a 3D profile of the object and characterizing its surface, composition, shape and structure. Comet interceptor is due to launch in 2028 according to ESA.

Famous comets

Halley's Comet is likely the most famous comet in the world, even depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry that chronicled the Battle of Hastings of 1066. It becomes visible to the naked eye about every 75 years when it nears the sun. When Halley's Comet zoomed near Earth in 1986, five spacecraft flew past it and gathered unprecedented details, coming close enough to study its nucleus, which is normally concealed by the comet's coma.

The roughly potato-shaped, 9-mile-long (15 km) comet contains equal parts ice and dust, with some 80% of the ice made of water and about 15% of it consisting of frozen carbon monoxide. Researchers believe other comets are chemically similar to Halley's Comet. The nucleus of Halley's Comet was unexpectedly extremely dark black — its surface, and perhaps those of most others, is apparently covered with a black crust of dust over most of the ice, and it only releases gas when holes in this crust expose ice to the sun.

The comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 collided spectacularly with Jupiter in 1994, with the giant planet's gravitational pull ripping the comet apart for at least 21 visible impacts. The largest collision created a fireball that rose about 1,800 miles (3,000 km) above the Jovian cloud tops as well as a giant dark spot more than 7,460 miles (12,000 km) across— about the size of the Earth — and was estimated to have exploded with the force of 6,000 gigatons of TNT.

A relatively recent, highly visible comet was Hale-Bopp, which came within 122 million miles (197 million km) of Earth in 1997. Its unusually large nucleus gave off a great deal of dust and gas — estimated at roughly 18 to 25 miles (30 to 40 km) across — appeared bright to the naked eye.

Comet ISON was expected to give a spectacular show in 2013. However, the sun-grazer did not survive its close encounter with the sun and was destroyed in December that year.

In 2021, scientists found what could be the largest comet ever seen. Comet C/2014 UN271 or Bernardinelli-Bernstein after its discoverers, University of Pennsylvania graduate student Pedro Bernardinelli and astronomer Gary Bernstein, was officially designated a comet on June 23. Astronomers estimate this icy body has a diameter of 62 miles to 124 miles (100 km to 200 km), making it about 10 times wider than a typical comet. The comet will make its closest approach to our planet in 2031 but will remain at quite a distance even then.

Additional reporting by Nola Taylor Redd, Space.com contributor.

Additional resources

- Watch this short European Space Agency animation: Life of a Comet.

- Explore NASA's current and previous comet missions.

- Discover why comets are important targets for space missions.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us

How To Draw A Comet For Kids

Source: https://www.space.com/comets.html

Posted by: webbtrus1947.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Draw A Comet For Kids"

Post a Comment